Listening to Country: A long journey behind the regeneration of Austin Downs

A WA rangeland story of patience, Traditional Owner knowledge and slow ecological repair.

Behind the carbon we often find heart warming stories of long term vision, love for the land, a desire to regenerate and restore, and the grit to make it happen.

Austin Downs Station in WA has all these elements. Jo Jackson King generously shared their family’s story with us: check it out here

What started as an irrigation investment in 2000 became a twenty five year journey of listening to Country, learning from Traditional Owners and slowly repairing a heavily degraded rangeland lease in the Murchison.

A landscape full of questions

When the Jacksons bought the property, they soon realised the wider landscape was more complex than it looked. Walking the country, comparing old records and studying plant remnants, they began asking difficult questions: when was the topsoil lost, how much grass had disappeared, and how degraded was the land really.

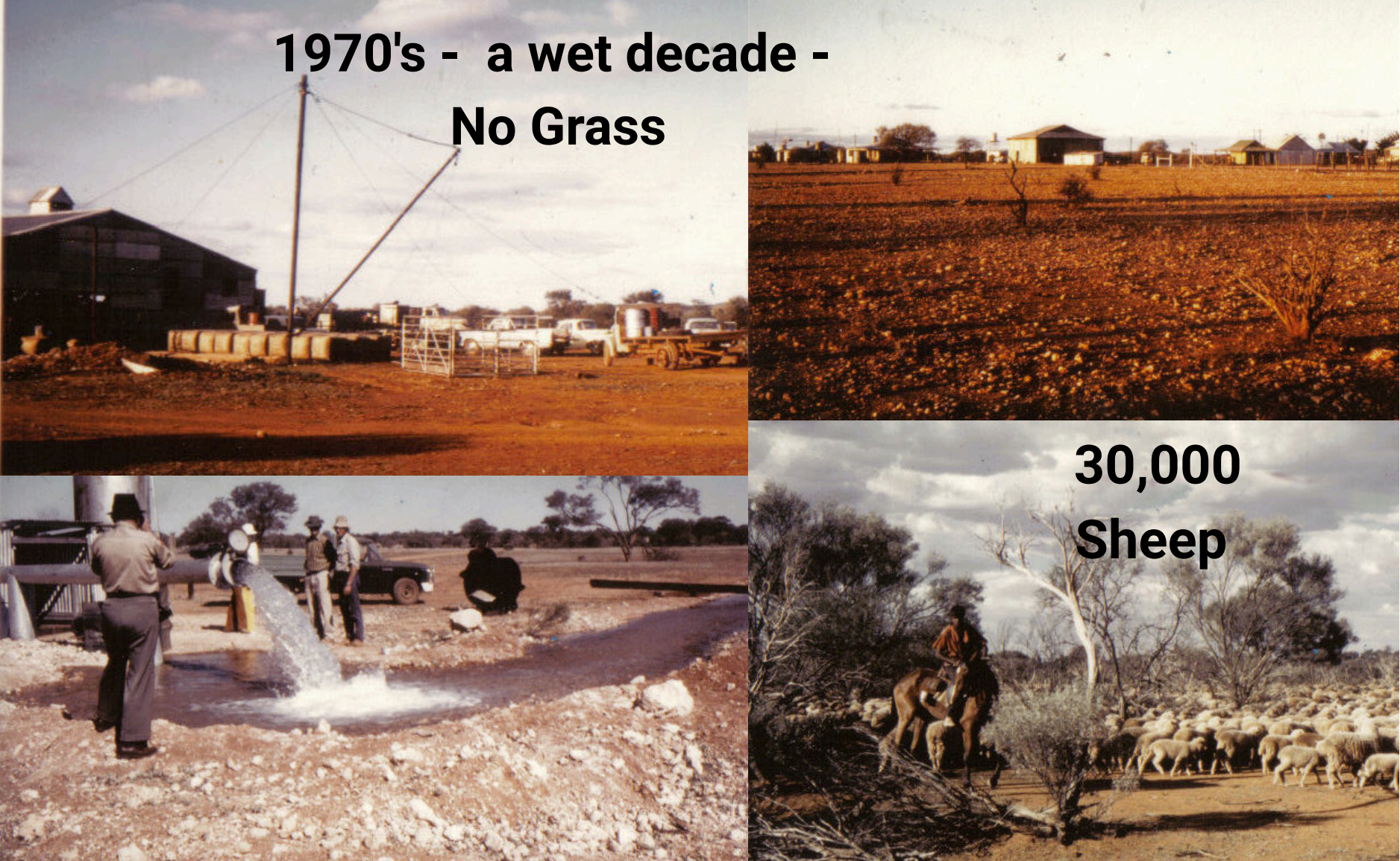

Conventional wisdom said the region was never true grass country, but evidence on the ground, old photographs, tussock remnants and stocking records, suggested otherwise. Tom and Barbara believed the country once held far more perennial grasses and palatable species than remembered.

Pictures from their story going back to the 70s when despite the rain there was hard cracked clay and no grass

Honouring Traditional Owners’ knowledge

As they learned the landscape’s puzzles, Tom’s understanding of Traditional Owners’ knowledge deepened. He described colonisation as “a wrecking ball through the longest piece of research in human history”, leaving stories, symbols and cultural sites as surviving lab notes.

Austin Downs sits on Wajarri and Yugunga Nya Country, connected by traditional trading routes for ochre. Birthing sites, gnamma hole maps and plant distributions all hinted at a once rich and functional ecosystem capable of supporting far more people and biodiversity than today.

Destocking and the long recovery

After purchase, the property was stocked at high levels following several good seasons: sheep, goats, kangaroos, donkeys and 62 artificial watering points across 167,000 hectares. But drought set in quickly.

By 2003, after realising the extent of decline, the Jacksons fully destocked and turned off most artificial waters. They spent nearly two decades earning their income off property while the rangeland rested.

Big rains in 2006 made the scale of degradation impossible to ignore. A two kilometre wide wash of topsoil rich water cut them off for weeks. Calculations showed that around 85% of rainfall had run off instead of soaking in. The land had lost its ability to function.

Yet even in this state, small signs of resilience appeared. After the 2006 and 2011-2013 rains, perennial grasses returned in pockets and species like Nardoo reemerged. Some areas transitioned from Rodanthe to grasses. Others stayed locked in drought.

“Listening to Country” becomes the approach

Guided by stories, symbols and cultural maps, the family reframed Austin Downs as a living record of First Nations land management interrupted. This changed their approach. They resisted early restocking, allowing plants to set seed. They upgraded fencing, shifted toward cattle, trialled mobile waters and moved stock according to land condition.

Some healthy transitions - e.g. Rodanthe to grasses - were observed

From 2008 Tom was advocating for carbon farming in the rangelands, and was co-author on a technical paper published in 2009, reviewing the economic and ecological sustainability of pastoralism in the Southern Rangelands of WA:

“Management of rangeland for increased prevalence of timber products [..] or sequestration of carbon is strongly linked to improved ecological productivity and biodiversity. Existing legislation procludes reward to land managers for adopting practices that would promote timber production and carbon sequestration.”

Carbon farming remained just over the horizon, but the big rains of 2011 and 2012 and then 2013 changed everything. Grass returned in wide patches, so once recovery was underway, they began careful restocking (keeping numbers low) and later registered a HIR (human induced regeneration) carbon project.

Carbon and biodiversity gains

By the time carbon methods became available, much of the early regeneration had already occurred. This means it was classed as ‘fully forested so was not allowed to be included as part of a carbon project.

But from 2018 onward the family aligned grazing practices with sequestration, keeping cattle mobile and favouring ground cover.

They also measured biodiversity improvement. Using Accounting for Nature (with Select Carbon), plus Bush Heritage and RSM for audit and verification, Austin Downs established a baseline that reflected real ecological gains, even in the paddocks they considered “poor”.

The results were deeply meaningful for Tom. Their ACCUs are now listed on the NXT Registry with the biodiversity baseline attached.

Funding the future

Carbon income helped but remained unreliable. The family began exploring diversification leases and renewable energy options on the property’s most degraded areas, although the pathway is still untested in pastoral WA and energy markets in remote regions are difficult.

Still, the work continues. The same patience, curiosity and long term view that carried Austin Downs through two decades of repair is steering its next chapter.

Read about it here

Austin Downs presentation uncompressed (Presentation) by Jo Jackson King

Want to know more?

Check out Dig it or plant it? Choosing the right carbon offset path, a closer look at pros and cons of tree planting versus soil carbon projects.

Unlock the Carbon Potential of your land?

Not sure where to start? Get a clear, data-backed measure of your land's carbon potential. From free snapshot reports to deep-dive assessments, we help you determine the best path forward.

Free Carbon Snapshot: Enter your address to see if a carbon project is viable for your land.

Project Explorer: View existing carbon projects and regional activity near you.

Browse the Learning Hub : Explore the full collection of articles at no cost.